The story behind my book ‘The Great Auk’s Great Escape’

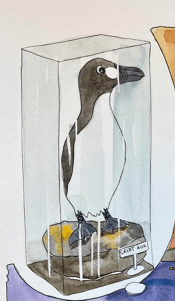

The only place you will see a great auk today is in a display case.

This striking black and white seabird stands behind glass in the galleries of some of our most prestigious museums – the Kelvingrove in Glasgow, Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland, and the Natural History Museum in London. It is a sad end for a creature that, until the 1800s, would have been a familiar sight on many north Atlantic islands.

Today, our national museums are committed to the conservation of endangered species, but in the early 19th century priorities were different, and the drive to obtain this rare bird’s eggs and skins for collections and exhibition almost certainly hastened its demise.

Several of the world’s last great auks were killed to be ‘preserved’ – but one of the last in Britain (and the very last one to be conclusively identified) escaped that fate, against the odds, in 1821.

By that time, great auk sightings had become rare even around Scotland’s remotest skerries. In St Kilda, where the birds had once been regular summer visitors, islanders must have recognised this lone creature’s value, when they spotted it on a ledge – and didn’t eat it.

The bird, which was considerably bigger than a gannet, with stubby wings and a beak like a razorbill’s, was captured by four youths in a rowing boat. They kept it alive and passed it on to Mr MacLellan, the tacksman (factor) of both St Kilda and the Isle of Scalpay (Harris), perhaps as a contribution towards rent.

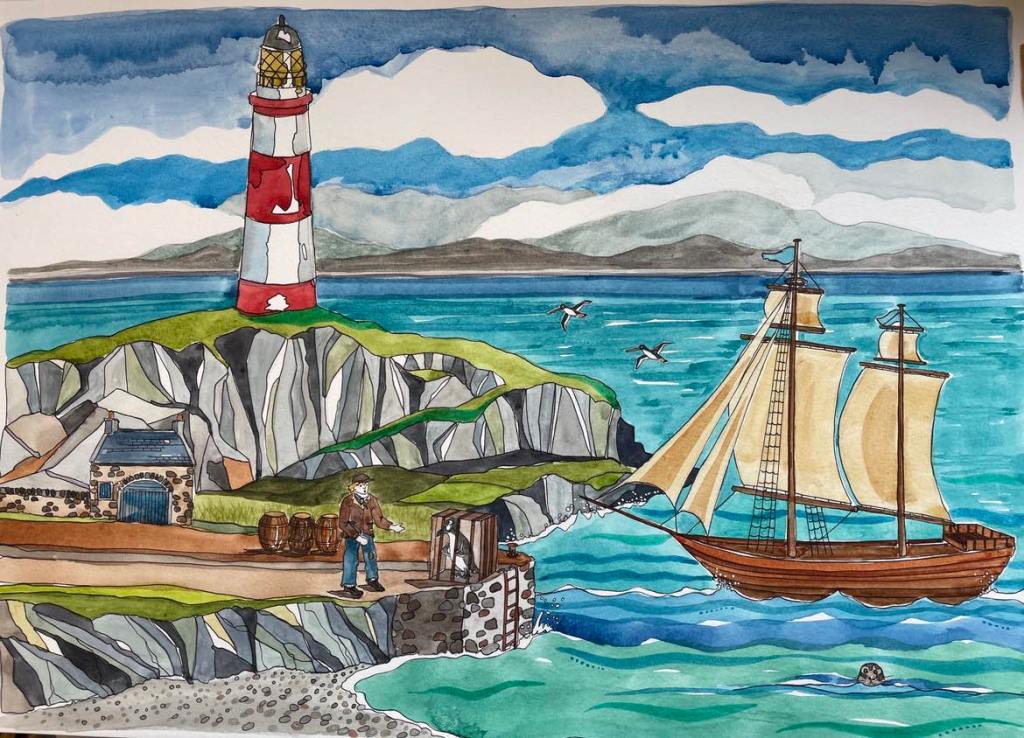

MacLellan took the bird back to Eilean Glas, a peninsula of Scalpay and the site of one of the Stevensons’ most iconic lighthouses.

Accounts of these events were collated by researchers who visited St Kilda decades afterwards and interviewed the surviving islanders (sources include R. Scott Skirving and Symington Grieve) and there are several variations on the details described, but the next part of the story is more clearly documented.

In August 1821, the engineer Robert Stevenson arrived on Scalpay, conducting his annual lighthouse inspection tour on board the Regent, a 66ft schooner. He was joined by his friend Rev. John Fleming, a respected naturalist who kept a journal of the voyage (published in the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal (Vol X) in 1824).

When the Regent left the island on August 18th, the great auk was on board, alive, and with its fate seemingly sealed – it was to become an exhibit in Edinburgh’s College Museum.

In what is one of the only documented descriptions of a live great auk, Fleming wrote:

“On the eve of our departure from this island, we got on board a live example of the Great Auk (Alca impennis)…A few white feathers were at this time making their appearance on the sides of its neck and throat, which increased considerably during the following week, and left no room to doubt that, like its conveners, the blackness of the throat feathers of summer is exchanged for white, during the winter season…The bill was black, with the rudiments of a single ridge, and the white line reaching to the eye was obvious.”

The bird’s condition, when brought aboard, was not good, and possibly not good enough to make it attractive to any new owner, so efforts were made to improve its condition, feeding it plenty of fish and – perhaps surprisingly – allowing it to go for a splash in the sea.

Fleming’s description of how this was achieved gives insight into what would happen later.

“It was emaciated, and had the appearance of being sickly, but, in the course of a few days, it became sprightly, having been plentifully supplied with fresh fish and permitted occasionally to sport in the water, with a cord fastened to one of its legs, to prevent escape. Even in this state of restraint, it performed the motions of diving and swimming under water, with a rapidity that set all pursuit from a boat at defiance.”

With its unusual cargo on board, and doubtless the object of curiosity to passengers and crew, the Regent’s tour continued. Fleming records spending the night in Lochmaddy, North Uist, before visiting Loch Scavaig on Skye, a walk up the Scuir of Eigg, and sailing into Fingal’s Cave, Staffa before visiting Iona, Islay and the Giant’s Causeway – finally finishing his expedition at the Mull of Kintyre on August 26th.

Rev. Fleming’s account ends there, with the great auk still on board, as he left to take the steam packet home from Campbeltown. It was at the yacht’s next lighthouse stop, at Pladda on the Isle of Arran, that plans went awry.

A Notice to Mariners and Fishermen, which appeared in the Glasgow Sentinel at the end of November that year, enlightens us about what happened next.

“A bird of rare species called the Great Auk, Alca Impennis of Linneus, has escaped from the ISLAND of PLADDA in the Firth of Clyde. Any person who shall find this Bird and give information to any of the Light-keepers at Pladda, Kintyre, Corsewell, Cumbra or to Captain Taylor, Lighthouse Store, Leith, will receive a REWARD OF TWO GUINEAs if alive, or ONE GUINEA if dead.”

While it was being given the opportunity to take a swim in the sea, with the rope tied around its leg as Fleming had described, the great auk had managed to get away (either breaking the rope, or slipping completely out of it). It vanished.

The reward posted for its recovery was a generous one, and the detail in the notice shows how keen the former captors were to reclaim it.

“The bird resembles a marrot (guillemot) or Razor bill in colour, being black above, with a narrow, white band across the wings, and white beneath, but is about the size of a Solan Goose (gannet). Its bill is about five inches in length, it stands and walks erect, and is strikingly marked with a large white ovel spot under each eye. It is perfectly tame and even docile when on land, but is extremely active and shy when in the water.

Despite the advertising, there was never another confirmed sighting of the auk.

Symington Grieve, author of The Great Auk, or Garefowl (published in 1885) reported that remains that could have been that great auk washed up in Gourock, on the Firth of Clyde, 60 miles north-east of the site of its disappearance, soon afterwards.

However, if the bird vanished at the end of August, and this advert appeared in mid-November, whoever posted it still had hope of its being found almost three months after the expedition ended.

There was another great auk, heralded as the last one in Britain, captured on St Kilda two decades later, in July 1840. This creature was reportedly found and caught on the sea stack, Stac al Armin (whereas the first was on Hirta) and accounts of its demise are also based on interviews with St Kildans years afterwards.

When a storm blew up, stranding the bird and its captors in a bothy, the men blamed the noisy auk for the violent weather, decided that it was a witch, and stoned it to death.

To me, one of the stranger aspects of the Eilean Glas great auk case is how little attention it has gained. It does features in books and studies, but often as a side note, and even John Fleming, the naturalist whose name is so closely associated with it, only spared the remarkable creature a few lines in a journal that devoted many pages Hebridean rock formations.

Google ‘Great Auk’ and ‘St Kilda’ and you will find a list of retellings of the ‘witch’ story. Of course, it is noteworthy because it is considered the last, and because of the macabre nature of its killing, but it still seems odd to me that there is so little folklore around the earlier story, which has its fair share of mystery and adventure too.

Perhaps this isn’t an accident. In a high society obsessed with egg collection and taxidermy, the capture ‘for science’ of a bird known to be on the brink of extinction must have been something of a coup. Its loss (particularly if the delivery had already been heralded) through a lapse as foolish as an unchecked rope, could have brought embarrassment to some of Scotland’s most influential men. Maybe there is little record of the incident because, with no prize, it was felt not worth discussing.

When I came across this case it captured my imagination for different reasons. In 1821 the loss of a valuable potential museum piece might have been viewed as a failure, but with today’s lens, the tale of a smart, beautiful creature who outwits its human captors, felt like one of hope.

We know that great auks were fast, strong swimmers, and I like to think of this one finding its way home to some inaccessible ledge where it could meet a mate for life, hatch an egg, and never encounter a human being again.

The story became the basis for a children’s picture book, The Great Auk’s Great Escape, which was published in 2024. Aimed at primary-aged children, it is a fictional re-imaging of how the auk’s escape might have happened, with some heroic involvement from the cabin boy.

The story is illustrated by Harris-based author Joceline Hildrey, whose passion for the landscape and wildlife of the Hebrides shows on every page.

I hope that the book can introduce the story of the great auk to children who will never see one alive, and that it will help them to view extinction both as a real, pressing threat, and one that they have the power to do something about. Perhaps it might inspire them to visit a great auk (one of the less than 80 mounts left) in a museum too.

It is 180 years since the last confirmed sighting of a live great auk. A nesting pair were shot to order off Eldey Island in south-west Iceland, in the summer of 1844. Though there are many species (including the great auks relative, the Atlantic puffin) at risk now, no other nesting British bird has become extinct since. Let the tales of the great auks be motivation for us to keep it that way.

The Great Auk’s Great Escape, by Louisa MacDougall, illustrated by Joceline Hildrey, is published by the Islands Book Trust islandsbooktrust.org. All images in this article are by Joceline Hildrey